Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears occur in both genders, but female athletes are at higher risk with college basketball and soccer female athletes having a threefold higher risk than their male counterparts. The effect of this discrepancy has been amplified in the past few decades as a result of the passage of Title IX in 1972 resulting in large increases in female athletes participation and participation at higher levels of competition. In 1972 there were 300,000 female high school athletes and in 2007 that number grew to three million. It is currently estimated that one in 100 female high school athletes and one in 10 female college athletes will sustain a serious knee injury each year. ACL tears occur most frequently in the act of landing or planting and cutting. They can occur with or without contact from an opposing player and female athletes are at higher risk of noncontact injury. Notoriously high risk sports include football, soccer, basketball, team handball and alpine ski racing. In females, the peak injury incidence occurs between ages 15 and 19. ACL tears do not heal but the ligament can be surgically reconstructed using harvested tendon or ligament from the patient or a deceased donor, although this has fallen out of favor in young athletes because of higher risk of re-rupture in donated tissue. Most medical experts recommend an ACL reconstruction for young athletes to restore knee stability allowing return to sport. The surgery is far from a perfect solution though, with athletes unable to return to sport for a minimum of 6-9 months while full recovery can take up to two years. For a young athlete whose social identity is tightly linked to their sport, the loss of their sport for this length of time can be devastating. In addition, about half of all ACL tears have associated cartilage injuries that are more challenging or impossible to fix. Lastly even with surgery, there bis evidence that over half of athletes sustaining an ACL tear will have evidence of knee arthritis starting within 12 years of injury. As a result there is great interest in preventing these injuries.

Anatomy

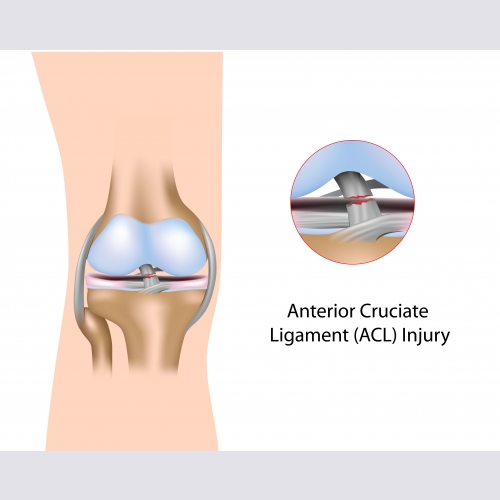

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is located in the middle of the knee starting on the posterior aspect of the distal femur (thigh bone) and attaching to the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia (leg bone). It prevents the tibia from moving forward and also helps prevent rotation of the tibia. Because the quadriceps muscle also pulls the tibia forward, strong quadriceps activation is associated with ACL injury. The hamstrings attach behind the tibia and help prevent the tibia from going forward. As a result strong hamstrings and specifically hamstrings that are strong relative to the quadriceps are associated with lowering the risk of ACL injury. Because body position is associated with ACL injuries, strong hip and trunk muscles and good control over those muscles in athletic situations is also associated with lowering the risk of injury. Causes of Injury There are a range of theories to explain the higher risk of injury in females. The effect of hormones, specifically estrogen, has been studied. There is evidence that high levels of estrogen can increase ligament laxity, and that increased laxity is associated with ACL tears. However, there is not consistent evidence that ACL tears occur at a specific time in the menstrualcycle. There is variability in joint laxity from person to person and those with loose knee ligaments are at higher risk for knee ligament injury. There is also evidence that those with smaller ACL’s and those with a tibia that slopes downward posteriorly are at higher risk but these anatomic variables are not easily modified, so these factors could identify somebody who is at higher risk, but fixing these issues is impossible or impractical. Fortunately there are muscle strength and biomechanical factors associated with ACL injury that are modifiable. One interesting finding is that before puberty, an ACL tear is rare and not more frequent in girls, but after puberty the girls’ risk increases significantly. Through puberty boys naturally increase their hamstring strength more than their quadriceps strength while girls develop stronger quadriceps and their hamstring strength changes very little. This creates a muscle imbalance in young women and “quadriceps dominance” places the ACL at higher risk. A number of biomechanical differences also increase the risk for females. Females are more likely to land with a knee that turns and bends inward, known as valgus alignment. This alignment is associated with increased risk. Females also tend to land from a jump with a more upright posture and less knee bend. This position facilitates quadriceps activation and inhibits hamstrings increasing ACL risk. These muscle imbalance and biomechanical issues are modifiable and are the primary target of ACL injury prevention programs.

Preventing Injury

A number of injury prevention (or more appropriated injury reduction) programs targeting proposed ACL risk factors have been developed including the FIFA 11+, PEP program, Sports Metrics and PEAKc. A number of features are common to each program including a dynamic warm up (actively moving through a set of stretches), a plyometrics section (jumping), an agility section (emphasizing balance with hopping and change of direction) and a strengthening section. Each program teaches lower risk movement patterns emphasizing proper (less valgus) alignment of the knee and hip specifically with landing and cutting, the activities most associated with ACL injury. Specific instructions for each program are accessible on-line.

Efficacy and Implementation of Injury Prevention Programs

Across a range of studies, most injury prevention programs reduce the risk of serious knee injuries by 50% or more. While girls are often the primary target, boys can also significantly reduce their risk with these programs. Age 14 or puberty is often identified as the appropriate time to start these programs and results for teens as opposed to college age players are the most dramatic. Improved compliance does improve outcomes. One study showed that the most compliant players had an 88% reduction in risk while the least compliant did not benefit and while many of the programs recommend training twice a week, at least one program with weekly training over the course of a year was effective. It takes time, probably at least six weeks, to begin seeing a reduction in injury risk so programs should start pre-season and be continued through the season to be most effective. Not only do injury prevention warm-ups reduce injury, but they also have been shown to increase balance, vertical jump and other measures of performance. Despite proven benefits of injury prevention programs, U.S. youth sports clubs have been slow to incorporate them. Sports physicians, physical therapists and certified athletic trainers all have a role in encouraging youth organizations to adopt these programs and studies have shown that if a health professional teaches the coach and/ or the athletes, the programs are completed more effectively. Education then “buy in” starting with the coaching directors and board members is an effective strategy to improve longerterm compliance and “marketing” these programs for both injury reduction and performance enhancement is both valid and proven to improve compliance.